Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Is it just me, or have conservatives begun to take the Bush administration for granted? A potentially great justice like Samuel Alito is confirmed, and by following a brilliant strategy crafted by the White House, he is confirmed in a way that makes the threat of filibuster weaker not stronger and helps ignites a civil war in the leftist camp that threatens to tear up the Democratic base. But most bloggers don't seem to care all that much.

Monday, January 30, 2006

"How can you help people if you don't know the right stories?"

I went to see "Walk the Line" this weekend. I'm a sucker for any "redemption of a man down and out" tale and this was no exception. The music side of it was a bit weak -- especially compared to "Coal Miner's Daughter" -- but the acting was excellent and the script-writing superb.

One of my favorite lines came right up in the beginning when the brothers J.R. and Jack are talking in bed. J.R. asks Jack why he's so good, and Jack replies he ain't and adds that anyway J.R.'s memorized Momma's hymnal. Jack then adds (and I'm paraphrasing), "If I'm going to be a preacher, I've got to know Scripture back to front. How can you help people if you don't know the right stories?"

Stories. Not doctrine. Not liturgy. Not historical background. Not proof-texts. All the rest -- they serve the stories of Scripture.

And this story reminded me of another I'm reading now: Kristin Lavransdatter, a classic trilogy by Sigrid Undset set in medieval Norway. Although it won the Nobel Prize in its day, it hasn't been so famous lately. An award-winning new translation by Tiina Nunnally has made it a bit well-known again. What does this have in common with "Walk the Line"? In both, the theme is the fearsome anarchy of romantic love. Ironically, it is not Johnny Cash's pills or the loathsome groupies that brings him to disaster, but his constant, unyielding love for June Carter. And yet that same unyielding love is what offers him a second chance.

In Kristin Lavransdatter, it is Kristin's unyielding, brutal, and utterly faithful passion for Erland, her lover and husband, that drives the mechanism of disaster. Because she was writing a book and not a movie, or because she was writing in Europe, not America, the land of second chances, or because she was a divorced Catholic, and not a divorced Southern Baptist, in which a theoretical belief in monogamy has long coexisted with a belief that the desires of the human heart can be recognized and formalized but not tamed -- for whatever reason, Sigrid Undset offers no hope of a second chance at happiness in worldly love. No, the machinery of punishment grinds inexorably, as each broken heart generates two more, and the spurned partners refuse to fade into the woodwork. "Walk the Line" speaks of grace and second chances, but Kristin Lavransdatter speaks of the continuing power of sin.

What is the result of the fall? Is it merely the separation of sex from love, the surrendering to baser instincts? Or is it our reckless faithfulness in blindly pursuing romantic love, regardless of how it hurts those around us?

For both, Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy.

One of my favorite lines came right up in the beginning when the brothers J.R. and Jack are talking in bed. J.R. asks Jack why he's so good, and Jack replies he ain't and adds that anyway J.R.'s memorized Momma's hymnal. Jack then adds (and I'm paraphrasing), "If I'm going to be a preacher, I've got to know Scripture back to front. How can you help people if you don't know the right stories?"

Stories. Not doctrine. Not liturgy. Not historical background. Not proof-texts. All the rest -- they serve the stories of Scripture.

And this story reminded me of another I'm reading now: Kristin Lavransdatter, a classic trilogy by Sigrid Undset set in medieval Norway. Although it won the Nobel Prize in its day, it hasn't been so famous lately. An award-winning new translation by Tiina Nunnally has made it a bit well-known again. What does this have in common with "Walk the Line"? In both, the theme is the fearsome anarchy of romantic love. Ironically, it is not Johnny Cash's pills or the loathsome groupies that brings him to disaster, but his constant, unyielding love for June Carter. And yet that same unyielding love is what offers him a second chance.

In Kristin Lavransdatter, it is Kristin's unyielding, brutal, and utterly faithful passion for Erland, her lover and husband, that drives the mechanism of disaster. Because she was writing a book and not a movie, or because she was writing in Europe, not America, the land of second chances, or because she was a divorced Catholic, and not a divorced Southern Baptist, in which a theoretical belief in monogamy has long coexisted with a belief that the desires of the human heart can be recognized and formalized but not tamed -- for whatever reason, Sigrid Undset offers no hope of a second chance at happiness in worldly love. No, the machinery of punishment grinds inexorably, as each broken heart generates two more, and the spurned partners refuse to fade into the woodwork. "Walk the Line" speaks of grace and second chances, but Kristin Lavransdatter speaks of the continuing power of sin.

What is the result of the fall? Is it merely the separation of sex from love, the surrendering to baser instincts? Or is it our reckless faithfulness in blindly pursuing romantic love, regardless of how it hurts those around us?

For both, Lord have mercy, Christ have mercy.

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

Some Gut Feelings and Observations on Christian Unity

This week is the week of prayer for Christian ecumenism and it must be working since even Josh S. has recently declared his conviction that with regard to Christians in other church bodies, "We must see them and treat them as our friends, as fellow members of Christ." His discussion of Greenslade's Schism in the Early Church has raised some important points. (And I would like to thank Bill Tighe for sending me a copy. Thanks, Bill!) What follows is a few observations on Christian unity, that over the years I have found myself unable to avoid:

1) Greenslade (and Josh S.) are right: the idea of baptism being valid outside the church is absurd theologically. If Lutherans recognize Catholic or Baptist baptisms (and we do), then we recognize that they are part of the Christian church. If we deny Mormon baptisms then we are saying they are not part of the Christian church.

2) Everybody believes in the concept of the invisible church, even Catholics and Orthodox. Orthodox are fond of saying, "We know there is no salvation outside the church, but what we don't know is where the church ends." This is a doctrine of the invisible church -- if you don't know where it ends then you can't "see" it, and what can't be "seen" is invisible. Nobody (or at least nobody that anybody takes seriously) believes that my communion, my visible church, defines the limit of the only-saving church. So if the invisible church idea is a Reformation innovation, then it is a Reformation innovation that the church at large has come to accept. The most fundamental dispute remaining is the question of whether there is really a visible church, in the sense of an organization with the power of dispensing salvation through baptism and the power of the keys. Catholics, Orthodox, and (Augsburg) Evangelicals say yes, Reformed and revivalistic Christians say no.

3) Putting 1 and 2 together, everyone therefore agrees that valid baptism defines the visible church as it is understood in the Nicene Creed. For a Catholic to say, yes the Augsburg Evangelicals have valid baptisms, and yes, they may be saved through such baptism, but no they are not part of the visible church because they don't have true bishops or in communion with the Pope, is simply to a) contradict themselves and say salvation is visible because it depends on baptism but is invisible because you can't "see" where the church is, and b) to go against the plain meaning of the Nicene Creed. One church and one baptism for the remission of sins, which was always understood at the time as meaning that if you are not baptized in the true church you go to hell on your death. (Exceptions about baptism of blood or desire don't alter the case.) Ditto, of course, if the Augsburg Evangelicals say that about the Roman Catholics.

4) The New Testament church knows nothing of people who insist on remaining outside the one, true, visible church who are not going to hell. This means two things: 1) if you say a convinced member of a Christian church is not going to hell, then you mean that this Christian's church body in which he or she is baptized and takes communion is a limb of the visible church. It also means 2) that no rule for how Augsburg Evangelicals should treat Presbyterians, or Orthodox should treat Catholics can be established simply by consulting the Scriptures (or church tradition), unless you want to go with the "don't even eat with them" rule of 1 Corinthians 6.

5) The idea that the Islamic persecution of the Armenians and Copts is not a Christian issue, is absurd. This in turn means that the Armenians and Copts are in fact Christians. ( What I mean is, Islamic persecution of Baha'is in Iran or Chinese persecution of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, is a human rights issue, but not a Christian issue. But if we say Coptic Christians being persecuted in Egypt is something more than a human rights issue to us who call ourselves Christian, then we are saying the Copts are Christian.) And since they reject Chalcedon, the idea that Chalcedon is a defining creed of Christians is thereby shown to be false (or rather it is shown we don't really believe it). The Nicene creed on the other hand retains that status -- it is an amazing law of history that churches which explicitly reject it either disappear (the Arians) or rapidly become clearly non-Christian (the Unitarians). If this is the case, then the great schism (that is the first schism between Christians that remained unresolved) took place in the fifth century, not in the eleventh, or the sixteenth century. I may hold to Chalcedon and to the Augsburg confession, but I cannot legitimately make one or the other a defining mark of the extent of the Christian church.

6) At least for those who believe in the visible church, the idea of "restoration" is a heresy. The one crystal-clear thing we know about baptism and absolution is, "you can't baptize or absolve yourself." This means that if I was validly baptized, my baptism must have been performed in a limb of the Christian church. And that body must itself have received baptized from another such body, all the way back to the apostles. As a result, any limb of the visible church must recognize the church-ness of the body from which it came. Once a body loses Christianity (say, the Unitarians, or the Mormons) it cannot be "restored". If the Reformed then recognize baptism as a visible sacrament of salvation, they will by that same token have to recognized the Catholic church as a Christian church and abandon the idea of the "Great Apostasy."

7) Everyone agrees that apostolic succession by itself has no influence on orthodoxy. Within the Protestant world the Anglican communion and the Church of Sweden are proof enough. But within the non-Protestant world, Catholics are committed to apostolic succession not being meaningful apart from communion with the Pope, Orthodox that it is not meaningful apart from the seven ecumenical councils, the Armenians and the Copts that it is not meaningful apart from rejecting Chalcedon, and so on. To put it differently, everyone who believes in apostolic succession is in practice committed to the viewpoint that in the past vast numbers of validly ordained Christian bishops have taken themselves and their flock into schism, and that numerous ones have also taken themselves and their flock into heresy, but that no one who holds to this particular church's "extra-apostolic succession" principle (such as Papal communion, etc.) has ever gone into schism or heresy.

Now all of this will strike professed believers in the Pontificator's Fourth Law ("A church that does not understand itself as the Church, outside of which there is no salvation, is not the Church but a denomination or sect") as a recycling of the exploded "branch theory" but of course, as was already pointed out in 1) and 2) neither he nor any non-Feneyite Catholic actually believes what they claim to believe in. Rather they only pretend to believe it, but deny it everytime they in good conscience eat with or pray with a non-"whatever their church is" Christian.

Crossposted at Here We Stand

1) Greenslade (and Josh S.) are right: the idea of baptism being valid outside the church is absurd theologically. If Lutherans recognize Catholic or Baptist baptisms (and we do), then we recognize that they are part of the Christian church. If we deny Mormon baptisms then we are saying they are not part of the Christian church.

2) Everybody believes in the concept of the invisible church, even Catholics and Orthodox. Orthodox are fond of saying, "We know there is no salvation outside the church, but what we don't know is where the church ends." This is a doctrine of the invisible church -- if you don't know where it ends then you can't "see" it, and what can't be "seen" is invisible. Nobody (or at least nobody that anybody takes seriously) believes that my communion, my visible church, defines the limit of the only-saving church. So if the invisible church idea is a Reformation innovation, then it is a Reformation innovation that the church at large has come to accept. The most fundamental dispute remaining is the question of whether there is really a visible church, in the sense of an organization with the power of dispensing salvation through baptism and the power of the keys. Catholics, Orthodox, and (Augsburg) Evangelicals say yes, Reformed and revivalistic Christians say no.

3) Putting 1 and 2 together, everyone therefore agrees that valid baptism defines the visible church as it is understood in the Nicene Creed. For a Catholic to say, yes the Augsburg Evangelicals have valid baptisms, and yes, they may be saved through such baptism, but no they are not part of the visible church because they don't have true bishops or in communion with the Pope, is simply to a) contradict themselves and say salvation is visible because it depends on baptism but is invisible because you can't "see" where the church is, and b) to go against the plain meaning of the Nicene Creed. One church and one baptism for the remission of sins, which was always understood at the time as meaning that if you are not baptized in the true church you go to hell on your death. (Exceptions about baptism of blood or desire don't alter the case.) Ditto, of course, if the Augsburg Evangelicals say that about the Roman Catholics.

4) The New Testament church knows nothing of people who insist on remaining outside the one, true, visible church who are not going to hell. This means two things: 1) if you say a convinced member of a Christian church is not going to hell, then you mean that this Christian's church body in which he or she is baptized and takes communion is a limb of the visible church. It also means 2) that no rule for how Augsburg Evangelicals should treat Presbyterians, or Orthodox should treat Catholics can be established simply by consulting the Scriptures (or church tradition), unless you want to go with the "don't even eat with them" rule of 1 Corinthians 6.

5) The idea that the Islamic persecution of the Armenians and Copts is not a Christian issue, is absurd. This in turn means that the Armenians and Copts are in fact Christians. ( What I mean is, Islamic persecution of Baha'is in Iran or Chinese persecution of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, is a human rights issue, but not a Christian issue. But if we say Coptic Christians being persecuted in Egypt is something more than a human rights issue to us who call ourselves Christian, then we are saying the Copts are Christian.) And since they reject Chalcedon, the idea that Chalcedon is a defining creed of Christians is thereby shown to be false (or rather it is shown we don't really believe it). The Nicene creed on the other hand retains that status -- it is an amazing law of history that churches which explicitly reject it either disappear (the Arians) or rapidly become clearly non-Christian (the Unitarians). If this is the case, then the great schism (that is the first schism between Christians that remained unresolved) took place in the fifth century, not in the eleventh, or the sixteenth century. I may hold to Chalcedon and to the Augsburg confession, but I cannot legitimately make one or the other a defining mark of the extent of the Christian church.

6) At least for those who believe in the visible church, the idea of "restoration" is a heresy. The one crystal-clear thing we know about baptism and absolution is, "you can't baptize or absolve yourself." This means that if I was validly baptized, my baptism must have been performed in a limb of the Christian church. And that body must itself have received baptized from another such body, all the way back to the apostles. As a result, any limb of the visible church must recognize the church-ness of the body from which it came. Once a body loses Christianity (say, the Unitarians, or the Mormons) it cannot be "restored". If the Reformed then recognize baptism as a visible sacrament of salvation, they will by that same token have to recognized the Catholic church as a Christian church and abandon the idea of the "Great Apostasy."

7) Everyone agrees that apostolic succession by itself has no influence on orthodoxy. Within the Protestant world the Anglican communion and the Church of Sweden are proof enough. But within the non-Protestant world, Catholics are committed to apostolic succession not being meaningful apart from communion with the Pope, Orthodox that it is not meaningful apart from the seven ecumenical councils, the Armenians and the Copts that it is not meaningful apart from rejecting Chalcedon, and so on. To put it differently, everyone who believes in apostolic succession is in practice committed to the viewpoint that in the past vast numbers of validly ordained Christian bishops have taken themselves and their flock into schism, and that numerous ones have also taken themselves and their flock into heresy, but that no one who holds to this particular church's "extra-apostolic succession" principle (such as Papal communion, etc.) has ever gone into schism or heresy.

Now all of this will strike professed believers in the Pontificator's Fourth Law ("A church that does not understand itself as the Church, outside of which there is no salvation, is not the Church but a denomination or sect") as a recycling of the exploded "branch theory" but of course, as was already pointed out in 1) and 2) neither he nor any non-Feneyite Catholic actually believes what they claim to believe in. Rather they only pretend to believe it, but deny it everytime they in good conscience eat with or pray with a non-"whatever their church is" Christian.

Crossposted at Here We Stand

Sunday, January 22, 2006

I Love Swim Meets

My son Jeff is on his high school swim team. Never having been athletic myself and having attended a high school were athletics were poorly organized and worse attended, I was surprised how much I love going to sports meets and cheering. This Saturday, our town's South and North High Schools had their annual big meet. Although South (Jeff's team) got clobbered at the boy's varsity level, he made some great times. I was proud that as a freshman, he was already on the varsity team.

I love all the funny rituals about swim meets:

1) The way one of the refs fires a shot when the lead swimmer in the 500 yard freestyle starts on the last two laps.

2) The way the boys' hair ends up looking like a birds nests after so much chlorinated water

3) The way they dye their hair -- bleached, or blue, or orange -- near the end of the season and then shave it off before sectionals.

4) The way they throw the coach in the water after a big meet.

5) The way excited kids pound the boards while waiting for a relay swimmer to come in.

6) The way you know you're an experienced parent because you walk into the building from out side wearing a short-sleeve shirt under your parka on cold days.

7) The way all the parents clap and cheer extra hard to show support when a struggling junior varsity swimmer finally finishes the race.

Friday, January 20, 2006

Where Does the Money Go in a Dual Income Family?

As I mentioned before, Harvard Magazine almost always has an unintentionally enlightening article, one that makes you say, "Well, yes, follow that thought through and you might get somewhere." Typically it concerns some issue where social science is demonstrating a deletrious effect of lifestyle changes which the magazine is compelled by its political stance to treat as beyond question.

So it is in this case.

In an article by Elizabeth Warren, the author talks of the "Middle Class on the Precipice," specifically referring to the dual-income family. Her argument is that the dual-income family model of economic life is far less secure than the former single-income family model that prevailed until 1970 or so.

Scholars, policymakers, and critics of all stripes have debated the social implications of these changes, but few have looked at their economic impact. Today the median income for a fully employed male is $41,670 per year (all numbers are inflation-adjusted to 2004 dollars)—nearly $800 less than his counterpart of a generation ago. The only real increase in wages for a family has come from the second paycheck earned by a working mother. With both adults in the workforce full-time, the family’s combined income is $73,770—a whopping 75 percent higher than the median household income in the early 1970s.

One good point the article makes is a single-income family can respond to a loss of the breadwinner's income (for whatever reason: death, injury, laid-off, fired, etc.) by sending the other parent into the paid labor force. Dual-income families don't have that option. In other word, single-income families work with a kind of discipline of deliberately keeping half of its potential labor force in reserve "for a rainy day," so to speak.

She also points out the tilting of the balance in the credit market from the debtors to the creditors, aided by Congress:

Since the early 1980s, the credit industry has rewritten the rules of lending to families. Congress has turned the industry loose to charge whatever it can get and to bury tricks and traps throughout credit agreements. Credit-card contracts that were less than a page long in the early 1980s now number 30 or more pages of small-print legalese. In the details, credit-card companies lend money at one rate, but retain the right to change the interest rate whenever it suits them. They can even raise the rate after the money has been borrowed—a practice once considered too shady even for a back-alley loan shark. When they think they have been cheated, customers can be forced into arbitration in locations thousands of miles from home. Some companies claim that they can repossess anything a customer buys with a credit card.

Smart people will avoid credit-card debt like dead birds in Turkey, but lots of people aren't smart, and the Bible tells us that God hates, yes HATES those who take advantage of their naivete. Even though they failed, we should be thankful for men like retired congressman Henry Hyde who tried to speak up for the debtors in the new bankruptcy law (and I know about the fraudulent use of bankruptcy; I know of a local millionaire of notoriously lax business ethics who regularly uses it to get out of inconvenient debts. Throw the book at him and people like him, but don't wink at the credit companies' loan sharking practices.)

Professor Warren also makes a good point about retirement risk being shifted on to the backs of families:

During the same period, families have been asked to absorb much more risk in their retirement income. In 1985, there were 112,200 defined-benefit pension plans with employers and employer groups around the country; today their number has shrunk to 29,700 such plans, and those are melting away fast. Steelworkers, airline employees, and now those in the auto industry are joining millions of families who must worry about interest rates, stock market volatility, and the harsh reality that they may outlive their retirement money. For much of the past year, President Bush campaigned to move Social Security to a savings-account model, with retirees trading much or all of their guaranteed payments for payments contingent on investment returns.

Now with these issues of retirement we have to remember that a defined benefit plan isn't a human right or a gift from heaven. Like many of the institutions that buttressed the security of the single-income families in the 1950s and 1960s they were created by unions, reformers (mostly women), and Democratic administrations who were animated by the ideal of the secure, home-centered, single-income family. (You can read more about this lost legacy of pro-family activism here.) Sadly their efforts were not accompanied by a similar focus on creating a pro-family culture, and so the result of the security and stability of the fifties was to create a generation that took it all for granted (Jeshurun grew fat and kicked . . .)

But unfortunately a good part of her article also aims to make the case that the dual-income model is irreversible (of course!), and driven by "rising prices for essentials as men’s wages remained flat." Actually though, the statistics she presents tell quite a different story. The only essential item that people are spending more on (and boy, are they spending more on it!) is housing. The only other major increases in the average budget are taxes, child care, and cars.

First she argues that families today are not living more luxuriously than in 1970; they are actually spending less on clothing, food, and household applicances:

. . . the average family of four today spends 33 percent less on clothing than a similar family did in the early 1970s. Overseas manufacturing and discount shopping mean that today’s family is spending almost $1,200 a year less than their parents spent to dress themselves. . . . Today’s family of four actually spends 23 percent less on food (at-home and restaurant eating combined) than its counterpart of a generation ago. The slimmed-down profit margins in discount supermarkets have combined with new efficiencies in farming to cut more costs for the American family. Appliances tell the same picture. . . . manufacturing costs are down, and durability is up. Today’s families are spending 51 percent less on major appliances than their predecessors a generation ago.

Even when we factor in the "23 percent more—a whopping extra $180 annually" spend on entertainment and the $300 more spent on computers, the total spent on all the above mentioned items combined is less for today's dual-income family that it is for 1970's single income family.

It's worth interjecting here that the savings in food and clothing are something which we can attribute to the Wal-Marts and Sam's Clubs of the world. Greater efficiency in the retail market has made a real difference to peoples' incomes.

So why are families today spending so much more? In a word, bigger houses and higher taxes, although the author struggles mightily to obscure the fact:

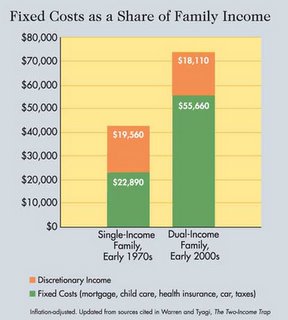

The data can be summarized in a financial snapshot of two families, a typical one-earner family from the early 1970s compared with a typical two-earner family from the early 2000s. With an income of $42,450, the average family from the early 1970s covered their basic mortgage expenses of $5,820, health-insurance costs of $1,130 and car payments, maintenance, gas, and repairs of $5,640. Taxes claimed about 24 percent of their income, leaving them with $19,560 in discretionary funds. That means they had about $1,500 a month to cover food, clothing, utilities, and anything else they might need—just about half of their income.

By 2004, the family budget looks very different. As noted earlier, although a man is making nearly $800 less than his counterpart a generation ago, his wife’s paycheck brings the family to a combined income that is $73,770—a 75 percent increase. But higher expenses have more than eroded that apparent financial advantage. Their annual mortgage payments are more than $10,500. If they have a child in elementary school who goes to daycare after school and in the summers, the family will spend $5,660. If their second child is a pre-schooler, the cost is even higher—$6,920 a year. With both people in the workforce, the family spends more than $8,000 a year on its two vehicles. Health insurance costs the family $1,970, and taxes now take 30 percent of its money. The bottom line: today’s median-earning, median-spending middle-class family sends two people into the workforce, but at the end of the day they have about $1,500 less for discretionary spending than their one-income counterparts of a generation ago.

Let's put this in tabular form in order of decreasing magnitude:

Mortgage then: $5,820; now: over $10,500 > + over $4,680

Taxes then: $10,188 (24% of income); now: $22,131 (30%) > +11,943 [since we generally agree taxes should be proportional to income this is misleading; had the tax rate stayed 24% per average family, today's tax bill would have been $4,426 lower].

Health insurance then: $1,130; now: $1,970 > +840

Even I was rather astounded by how really insignificant health insurances increases are compared to tax increases.

The other increasing expenditures -- for child care and for a second car -- are (at least in part) entailed by the decision to be a dual-income family:

Child care expenses then: $170*; child care expenses now: $5,660 (school age) -$6,920 (pre-school) > +$5,490 to $6,750

Car expenses then: $5,640 (for one car); now: over $8,000 (for two) > + over $2,360 [note the apparent implication that in real terms cars have gotten cheaper]

So while Professor Warren concludes that the dual-income family is a victim of forces beyond its control, and will eventually demand political action to reduce risk, what I conclude is that:

1) As long as you are willing to live in a small house and own one car, the single-income family makes as much sense as it ever did.

2) The desire for bigger houses is the main driving force behind the dual-income family.

And I can't avoid another query: is the flood of relatively unskilled female workers into the labor market keeping wages soft?

Tim Bayly has put up a very interesting post on big houses here. He questions why families with fewer children need more space. And if they don't need it, is it not squandering to buy it? What he doesn't mention is Isaiah 5:8-9:

Woe unto them that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place, that they may be placed alone in the midst of the earth! In mine ears said the LORD of hosts, Of a truth many houses shall be desolate, even great and fair, without inhabitant.

Why woe to them? Because they have done injustice to seize other men's fields? Certainly. But is there not something antisocial in the very desire to "be placed alone in the midst of the earth"? And does not the desire for bigger houses drive the desire to move to the outskirts of town, which makes a second car necessary, thus creating the other big drain on the family income?

My conclusion is hopeful, though: economize on your house, and don't buy a second car, and a single-income family has a realistic chance of achieving the financial security and stability that so many dual-income families seek in vain. The government may not be helping, but most of our financial future is in our own hands, and following the traditional rules of life are the key to that future. (Gee, sounds like Proverbs!)

* Derived by subtracting all the other figures

Labels: families, family values

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

How to Approach Holy Communion

As we have seen Luther made much of the idea of the Lord's Supper as Christ's last will and testament. In anti-Reformed/revivalistic polemic, this idea is often used to emphasize how the words of institution were serious and solemn and hence should treated solemnly and not juggled with word tricks. True enough, and Luther often makes that point in later anti-Zwinglian polemics. But he first emphasized the idea of testament to make a more significant theological point: that the Supper is a promise we receive, not a work we do.

If the Lord's Supper is a promise, then a number of very practical issues come out of this. The first has to do with preparation. As the Small Catechism says of the Sacrament of the Altar:

Fasting and bodily preparation are indeed a fine outward training; but he is truly worthy and well prepared who has faith in these words, 'Given and shed for you for the remission of sins.'

This theme too goes back to the Babylonian Captivity of the Church:

If the mass is a promise, as has been said, it is to be approached, not with any work or strength or merit, but with faith alone (p. 149).

Herefrom you will see that nothing else is needed for a worthy holding of mass than a faith that confidently relies on this promise, believes Christ to be true in these words of His, and doubts not that these infinite blessings have been bestowed upon it. Hard on this faith there follows, of itself, a most sweet stirring of the heart, whereby the spirit of man is enlarged and waxes fat -- that is love, given by the Holy Spirit through faith in Christ -- so that he is drawn unto Christ, that gracious and good testator, and made quite another and a new man. Who would not shed tears of gladnes, nay well-nigh faint, for the joy he hath toward Christ, if he believed with unshaken faith that this inestimable promise of Christ belonged to him! How could one help loving so great a benefactor, who offers, promises, and grants, all unbidden, such great riches, and this eternal inheritance, to one unworthy and deserving of something far different (p. 149).

Note that here with the mention of love, Luther is slowly moving into the topic of what we do in the mass. This he will need to do to confute the views of the opponents who hold that the mass is primarily a work, in the sense 1) that we must prepare ourselves for it by fastings and other mortifications, 2) that it is the perfect prayer in which we pray to God ; and 3) that it is a sacrifice in which the priest mystically participates in the offering of Christ on the cross. All three of these things are classic statements of Catholicism, none of which is flat out rejected in all senses, but none of which may be admitted in the then-traditional sense if the idea of the Lord's Supper as Christ's promise and testament is to be retained.

Luther first explains the "do this" of the words of institution: what is it we are to do?

Therefore it is our one misfortune that we have many masses in the world, and yet none or but the fewest of us recognize, consider, and receive these promises and riches that are offered, although verily we should do nothing else in the mass with greater zeal (yea, it demands all our zeal) than set before our eyes, meditate, and ponder these words, these promises of Christ, which truly are the mass itself, in order to exercise, nourish, increase, and strengthen our faith by such daily rememberance. For this is what He commands, saying "This do in rememberance of me."

This should be done by the preachers of the Gospel, in order that this promise might be faithfully impressed upon the people and commended to them, to the awakening of faith in the same. But how many are there now who know that the mass is the promise of Christ? (p. 149-50).

He next deals explicitly with the idea of bodily preparation:

From this everyone will readily gather that the mass, which is nothing else than the promise, is approached and observed only in this faith, without which whatever prayers, preparations, works, signs of the cros, or genuflections are brought to it, are incitements to impiety rather than exercises of piety; for they who come thus prepared are wont to imagine themselves on that account justly entitled to approach the altar, when in reality they are less prepared than at any other time and in any other work, by reason of the unbelief which they bring with them. How many priests will you find every day offering the sacrifice of the mass, who accuse themselves of a horrible crime if they -- wretched men! -- commit a trifling blunder, such as putting on the wrong robe or forgetting to wash their hands or stumbling over their prayers; but that they neither regard nor believe the mass itself, namely, the divine promise -- this causes them not the slightest qualms of conscience. O worthless religion of this our age, the most godless and thankless of all ages!

Hence the only worthy preparation and proper use of the mass is faith in the mass, that is to say, in the divine promise. Whoever, therefore, is minded to approach the altar and to receive the sacrament, let him beware of approaching empty before the Lord God [note the allusion to the proverbial statement of Exodus 23:15, 34:20, and Deut. 16:16, "They shall not appear before the Lord empty," referring to the need for a sacrificial offering]. But he will appear empty unless he has faith in the mass, or in this new testament [note the meaning here, of new last will and testament]. What godless work that he could commit would be a more grievous crime against the truth of God, than this unbelief of his, by which, as much as in him lies, he convicts God of being a liar and maker of empty promises? (p. 151-52)

Now does Luther leave any trace of the traditional (but not Biblical) disciplines of fasting before the mass? Only in the sense that fasting itself, like all forms of bodily discipline, are good things for the restraining of gluttony and self-indulgence. The Christian is a soldier, and soldiers who let their bodily condition go to pot betray their commander, their comrades, and their flag. Thus, we should take seriously the Small Catechism's admonishment to fasting and bodily training, whether connected to the mass or not, but always keep faith as the one essential thing, just as Paul says in 1 Timothy 4:8:

For physical training is of some value, but godliness has value for all things, holding promise for both the present life and the life to come.

Some, not none. Fine outward training, not hypocritical and evil outward training. But faith in the promise of salvation is the foundation of all such useful physical training and outward discipline.

Next up: Ex opere operato and the benefit of the mass. And following that, the notion of sacrifice and in what to Luther the idolatry of the mass actually consisted.

If the Lord's Supper is a promise, then a number of very practical issues come out of this. The first has to do with preparation. As the Small Catechism says of the Sacrament of the Altar:

Fasting and bodily preparation are indeed a fine outward training; but he is truly worthy and well prepared who has faith in these words, 'Given and shed for you for the remission of sins.'

This theme too goes back to the Babylonian Captivity of the Church:

If the mass is a promise, as has been said, it is to be approached, not with any work or strength or merit, but with faith alone (p. 149).

Herefrom you will see that nothing else is needed for a worthy holding of mass than a faith that confidently relies on this promise, believes Christ to be true in these words of His, and doubts not that these infinite blessings have been bestowed upon it. Hard on this faith there follows, of itself, a most sweet stirring of the heart, whereby the spirit of man is enlarged and waxes fat -- that is love, given by the Holy Spirit through faith in Christ -- so that he is drawn unto Christ, that gracious and good testator, and made quite another and a new man. Who would not shed tears of gladnes, nay well-nigh faint, for the joy he hath toward Christ, if he believed with unshaken faith that this inestimable promise of Christ belonged to him! How could one help loving so great a benefactor, who offers, promises, and grants, all unbidden, such great riches, and this eternal inheritance, to one unworthy and deserving of something far different (p. 149).

Note that here with the mention of love, Luther is slowly moving into the topic of what we do in the mass. This he will need to do to confute the views of the opponents who hold that the mass is primarily a work, in the sense 1) that we must prepare ourselves for it by fastings and other mortifications, 2) that it is the perfect prayer in which we pray to God ; and 3) that it is a sacrifice in which the priest mystically participates in the offering of Christ on the cross. All three of these things are classic statements of Catholicism, none of which is flat out rejected in all senses, but none of which may be admitted in the then-traditional sense if the idea of the Lord's Supper as Christ's promise and testament is to be retained.

Luther first explains the "do this" of the words of institution: what is it we are to do?

Therefore it is our one misfortune that we have many masses in the world, and yet none or but the fewest of us recognize, consider, and receive these promises and riches that are offered, although verily we should do nothing else in the mass with greater zeal (yea, it demands all our zeal) than set before our eyes, meditate, and ponder these words, these promises of Christ, which truly are the mass itself, in order to exercise, nourish, increase, and strengthen our faith by such daily rememberance. For this is what He commands, saying "This do in rememberance of me."

This should be done by the preachers of the Gospel, in order that this promise might be faithfully impressed upon the people and commended to them, to the awakening of faith in the same. But how many are there now who know that the mass is the promise of Christ? (p. 149-50).

He next deals explicitly with the idea of bodily preparation:

From this everyone will readily gather that the mass, which is nothing else than the promise, is approached and observed only in this faith, without which whatever prayers, preparations, works, signs of the cros, or genuflections are brought to it, are incitements to impiety rather than exercises of piety; for they who come thus prepared are wont to imagine themselves on that account justly entitled to approach the altar, when in reality they are less prepared than at any other time and in any other work, by reason of the unbelief which they bring with them. How many priests will you find every day offering the sacrifice of the mass, who accuse themselves of a horrible crime if they -- wretched men! -- commit a trifling blunder, such as putting on the wrong robe or forgetting to wash their hands or stumbling over their prayers; but that they neither regard nor believe the mass itself, namely, the divine promise -- this causes them not the slightest qualms of conscience. O worthless religion of this our age, the most godless and thankless of all ages!

Hence the only worthy preparation and proper use of the mass is faith in the mass, that is to say, in the divine promise. Whoever, therefore, is minded to approach the altar and to receive the sacrament, let him beware of approaching empty before the Lord God [note the allusion to the proverbial statement of Exodus 23:15, 34:20, and Deut. 16:16, "They shall not appear before the Lord empty," referring to the need for a sacrificial offering]. But he will appear empty unless he has faith in the mass, or in this new testament [note the meaning here, of new last will and testament]. What godless work that he could commit would be a more grievous crime against the truth of God, than this unbelief of his, by which, as much as in him lies, he convicts God of being a liar and maker of empty promises? (p. 151-52)

Now does Luther leave any trace of the traditional (but not Biblical) disciplines of fasting before the mass? Only in the sense that fasting itself, like all forms of bodily discipline, are good things for the restraining of gluttony and self-indulgence. The Christian is a soldier, and soldiers who let their bodily condition go to pot betray their commander, their comrades, and their flag. Thus, we should take seriously the Small Catechism's admonishment to fasting and bodily training, whether connected to the mass or not, but always keep faith as the one essential thing, just as Paul says in 1 Timothy 4:8:

For physical training is of some value, but godliness has value for all things, holding promise for both the present life and the life to come.

Some, not none. Fine outward training, not hypocritical and evil outward training. But faith in the promise of salvation is the foundation of all such useful physical training and outward discipline.

Next up: Ex opere operato and the benefit of the mass. And following that, the notion of sacrifice and in what to Luther the idolatry of the mass actually consisted.

Monday, January 16, 2006

Emotional Downward Mobility

On Katie's Beer and Be Strong in the Grace, TK has been talking about how hard it is as a real parent in this real world to help your children navigate a culture that is often so antithetical to what is good and right. There's one thing to be said for the various versions of the fundamentalist or Christian ghetto approach: they make thinking about issues like this a lot easier: just ban movies and you don't have to decide whether the fairly explicit sex scenes in Excalibur, for example, outweigh the powerful and engrossing illustration of how Arthur's kingdom fell through adultery because from the beginning it was founded on adultery. Sometimes I worry that my own choices in what movies to rent from Blockbuster (and Excalibur is one I've decided is not appropriate) or what CD's to buy them from Borders may have a corrupting influence on my own children. It may seem like a new problem, but it's one Christian parents have faced from the beginning; and we can be happy that evils like dueling or a blooming career in the slave trade no longer beckon to our children.

In some ways, music is a much more difficult rapid to canoe than movies because so few of us oldsters have any real familiarity with the music our teenage children listen to. More so than movies, music is generation-specific. As an active and involved mom, TK appears to have more than most and has been mulling over her (step) nephew's love of Eminem. As a contribution to her questions, I'd like to suggest that Mary Eberstadt has a great essay that asks us to ask a different question:

The ongoing adult preoccupation with current music goes something like this: What is the overall influence of this deafening, foul, and often vicious-sounding stuff on children and teenagers? This is a genuinely important question, and serious studies and articles, some concerned particularly with current music’s possible link to violence, have lately been devoted to it. . . . Nonetheless, this is not my focus here. Instead, I would like to turn that logic about influence upside down and ask this question: What is it about today’s music, violent and disgusting though it may be, that resonates with so many American kids?

The answers she comes up with are provocative:

Baby boomers and their music rebelled against parents because they were parents — nurturing, attentive, and overly present (as those teenagers often saw it) authority figures. Today’s teenagers and their music rebel against parents because they are not parents — not nurturing, not attentive, and often not even there. This difference in generational experience may not lend itself to statistical measure, but it is as real as the platinum and gold records that continue to capture it. What those records show compared to yesteryear’s rock is emotional downward mobility. Surely if some of the current generation of teenagers and young adults had been better taken care of, then the likes of Kurt Cobain, Eminem, Tupac Shakur, and certain other parental nightmares would have been mere footnotes to recent music history rather than rulers of it.

To step back from the emotional immediacy of those lyrics and to juxtapose the ascendance of such music alongside the long-standing sophisticated assaults on what is sardonically called “family values” is to meditate on a larger irony. As today’s music stars and their raving fans likely do not know, many commentators and analysts have been rationalizing every aspect of the adult exodus from home — sometimes celebrating it full throttle, as in the example of working motherhood — longer than most of today’s singers and bands have been alive (emphasis added).

Read it all. After I did, I found that while I guess I'm still fairly prudish, I have more understanding of where our childrens' friends are coming from.

In some ways, music is a much more difficult rapid to canoe than movies because so few of us oldsters have any real familiarity with the music our teenage children listen to. More so than movies, music is generation-specific. As an active and involved mom, TK appears to have more than most and has been mulling over her (step) nephew's love of Eminem. As a contribution to her questions, I'd like to suggest that Mary Eberstadt has a great essay that asks us to ask a different question:

The ongoing adult preoccupation with current music goes something like this: What is the overall influence of this deafening, foul, and often vicious-sounding stuff on children and teenagers? This is a genuinely important question, and serious studies and articles, some concerned particularly with current music’s possible link to violence, have lately been devoted to it. . . . Nonetheless, this is not my focus here. Instead, I would like to turn that logic about influence upside down and ask this question: What is it about today’s music, violent and disgusting though it may be, that resonates with so many American kids?

The answers she comes up with are provocative:

Baby boomers and their music rebelled against parents because they were parents — nurturing, attentive, and overly present (as those teenagers often saw it) authority figures. Today’s teenagers and their music rebel against parents because they are not parents — not nurturing, not attentive, and often not even there. This difference in generational experience may not lend itself to statistical measure, but it is as real as the platinum and gold records that continue to capture it. What those records show compared to yesteryear’s rock is emotional downward mobility. Surely if some of the current generation of teenagers and young adults had been better taken care of, then the likes of Kurt Cobain, Eminem, Tupac Shakur, and certain other parental nightmares would have been mere footnotes to recent music history rather than rulers of it.

To step back from the emotional immediacy of those lyrics and to juxtapose the ascendance of such music alongside the long-standing sophisticated assaults on what is sardonically called “family values” is to meditate on a larger irony. As today’s music stars and their raving fans likely do not know, many commentators and analysts have been rationalizing every aspect of the adult exodus from home — sometimes celebrating it full throttle, as in the example of working motherhood — longer than most of today’s singers and bands have been alive (emphasis added).

Read it all. After I did, I found that while I guess I'm still fairly prudish, I have more understanding of where our childrens' friends are coming from.

Friday, January 13, 2006

Women Have Always Been More Religious

The theme of how the effeminacy of religion keeps driving men away from church is a wheel that keeps on getting reinvented. Leon Podles got a book out of it (review here, article-length summary here), as did David Morrow (review here, article-length summary here, whole web-site [!] here), and just recently both Tony Esolen and the iMonk have written good posts about different aspects of the issue. And the Bayly brothers have made this a focal point of their message to their churches and the larger church (check out the "archives by subject" under patriarchy, feminism, etc., here). Adair T. Lummis on the other hand, after confirming the trends in the Episcopal church, basically says, "So what? We don't need the jocks, and they don't need us."

I agree with a lot of what all of these authors say (except the last), but I just have to "but" into the conversation. My "but" here has to do with the historical narrative that is often attached to this topic. In it, the natural state of Christian bodies (or religions in general) is assumed to be an even sex-ratio of men and women. One then looks for a bad guy or practice that by over-sentimentalizing or over-feminizing Christianity drove out the men, and created the current "feminized" church. It might be Bernard of Clairvaux (Podles's bad guy), altar girls (Tony Esolen's focus), or prissy behavior codes (what the iMonk criticizes). One then reasserts the manliness of Christ, of the Old Testament, of God the Father, of the apostles and martyrs, and voila! a complete narrative of declension.

Historically I just don't think this works. Here's a few counter-examples:

1) Ever notice how many unattached women believers are specifically mentioned as being church pillars in the New Testament? Like Lydia in Philippi (Acts 16), the prominent Greek women in Berea (Acts 17:12), and Damaris in Athens (Acts 17:34), not to mention the women in Christ's band of followers. Now given the general tendency of Greco-Roman writings to subsume women under men, I think that if women and men are roughly equally represented in the sources, then women are likely rather over-represented in real life. Rodney Stark's fascinating study of the sociology of early Christianity concludes the same: the legendary New Testament church that conquered the Roman Empire was numerically a woman-dominated one.

2) William of Rubruck was a famous (well, at least famous in the circles I move in) missionary to the Mongol empire (expensive annotated version here; accessible paperback here) in the thirteenth century. Several of Genghis Khan's sons had married women from Christian peoples on the Mongol steppe (Kereyids especially) and several of his grandchildren had been raised by such Christian mothers. But what he found was that few if any of the Mongol men would identify with Christianity or be baptized, but that many of the empresses and princesses did.

3) And outside of Christianity altogether, the Greco-Roman geographer Strabo notices the same thing. He's discussing various opinions on certain verses of Homer's Iliad, book xii:1-6, in which Zeus turns away from the battles before Troy to Thrace (modern Bulgaria) and the nomads beyond:

When Zeus had driven against the [Achaian or Greek] ships the Trojans and Hector,

He left them besides these to endure the hard work and sorrow

Of fighting without respite, and himself turned his eyes shining

Far away, looking over the land of the Thracian riders

And the Mysians who fight at close quarters, and the proud Hippomolgoi ["mare-milkers"],

Eaters of curds [Galactophagoi], and the Abii ["resourceless ones"], most righteous of all men.

Strabo approves of those who say the Abii as "bereft" or "resourceless ones" were naturally most righteous, since it is only money, and economic development generally, that causes injustice. Central Eurasian nomads who live on mares and curds far from the ocean and the commerce that comes with it are thus naturally primitive and just. (It's a bit of a digression, but I can't help but cite him at some length, since it points up the oft-ignored anti-civilization strain in Greek thought, that is remarkably similar to much modern radical thought)

As for the term "Abii," one might interpret it as meaning those who are "without hearths" and "live on wagons" quite as well as those who are "bereft"; for since, in general, injustices arise only in connection with contracts and a two high regard for property, so it is reasonable that those who, like the Abii, live cheaply, on slight resources, should have been called "most just." In fact, the philosophers who put justice next to self-restraint strive above all things for frugality and personal independence; and consequently extreme self-restraint diverts some of them to the Cynical mode of life. . . .

Now wherein is it to be wondered at that, because of the widespread injustice connected with contracts in our country, Homer called "most just" and "proud" those who by no means spend their lives on contracts and money-getting but actually possess all things in common except sword and drinking-cup, and above all things have their wives and children in common, in the Platonic way? [The tragedian] Aeschylus, too, is clearly pleading the cause of the poet when he says about the Scythians: "But the Scythians, law-abiding, eaters of cheese made of mare’s milk." And this assumption even now still persists among the Greeks: for we regard the Scythians as the most straightforward of men and the least prone to mischief, as also far more frugal and independent of others than we are. And yet our mode of life has spread its change for the worse to almost all peoples, introducing among them luxury and sensual pleasures, and to satisfy these vices, base artifices that lead to innumerable acts of greed. So then, much wickedness of this sort has fallen on the barbarian peoples also, on the nomads as well as the rest; for as the result of taking up a seafaring way of life they not only have become morally worse, indulging in the practice of piracy and of slaying strangers, but also, because of their intercourse with many peoples, have partaken of the luxury and the peddling habits of those peoples. But though these things seem to conduce strongly to gentleness of manner, they corrupt morals and introduce cunning instead of the straightforwardness which I just now mentioned.

Far from being some new innovation of the left, the feeling that commerce and development is basically a bad thing, and that "we" (developed and civilized people) are the primary spreaders of this bad thing around the world, is deeply rooted in the classical tradition.

Anyway, back to our topic . . .

Strabo also mentions the view of Posidonius who says that Homer's Abioi ("bereft" or "resourceless folk") means specifically bereft of women. He also says these people in Homer were particularly religious, which draws Strabo's indignant reply:

. . . To regard as "both god-fearing and smoke-treaders [from the smoke of their many sacrifices]" those who are without women is very much opposed to the common notions on that subject; for all agree regarding the women as the chief founders of religion, and it is the women who provoke the men to the more attentive worship of the gods, to festivals, and to supplications, and it is a rare thing for a man who lives by himself to be found addicted to these things. See again what the same poet [Menander, the third century BC comic playwright] says when he introduces as speaker the man who is vexed by the money spent by the women in connection with the sacrifices: "The gods are the undoing of us, especially us married men, for we must always be celebrating some festival"; and again when he introduces the Woman-hater, who complains about these very things: "we used to sacrifice five times a day, and seven female attendants would beat the cymbals all round us, while others would cry out to the gods."

Based on a broad range of historical data and contemporary survey research, Rodney Stark and other researchers have concluded (summary here) that women are generally more religious than straight men. More controversially they also suggest that homosexual men act like women in this respect and homosexual women like men. In other words, any religious body has a natural tendency, if not checked by some other force, to be dominated by women and gay men.

What's the conclusion? Certainly those of us who believe that the Christian religion is about salvation, and that everyone, including high-testosterone jocks, need it, should be more inspired than ever to prevent the Gospel from being captured by the natural inclinations of the fallen heart, to make of it something that simply appeals to the feminine side of our sin-distorted natures. But on the other hand, where church attendance is voluntary, and not enforced by social custom or law, a certain predominance of women is not in itself a sign of spiritual ill-health.

Historically, what has often prevented religion from becoming a pink-color ghetto is the link of religion to the state and ethnicity. To the degree that a given church dominates a state or ethnic group, it then becomes compulsory (by law or social custom) for all, thus masking the tendency for greater feminine interest and participation. It is interesting that Eastern Orthodoxy and Judaism are more masculine in support than western Christianity, at least in the United States. He explained that by saying that they were uninfluenced by Bernard of Clairvaux's feminine spirituality. I wonder rather if the reason that in the United States, these two religious bodies are basically ethnic. If natural religion is strongly linked to the feminine, ethnic and national pride seem to be more masculine traits.

In William of Rubruck's report, he noted that the Mongol men did not wish to be called Christian precisely because they saw "Christian" as the name of an ethnic group:

Before we took our leave of Sartach [Sartaq, a great grandson of Genghis Khan, ruling in the Crimea], the aforesaid Coiac [a Syriac or "Nestorian" priest serving at Sartaq's court] together with many other scribes of the court said to us, "Do not say that our master [Sartaq] is a Christian [although rumor said he had been baptized], for he is not a Christian, but a Mongol." This is because the word Christianity appears to be the name of a race, and they are proud to such a degree that although perhaps they believe something of Christ, nevertheless they are unwilling to be called Christians, wanting their own name, that is, Mongol, to be exalted above every other name [chapter xvi].

If we are going to make religion purely voluntary and divorced from ethnicity or the state, then I think we are going to have to accept that masculine interest is going to be somewhat harder to sustain.

I agree with a lot of what all of these authors say (except the last), but I just have to "but" into the conversation. My "but" here has to do with the historical narrative that is often attached to this topic. In it, the natural state of Christian bodies (or religions in general) is assumed to be an even sex-ratio of men and women. One then looks for a bad guy or practice that by over-sentimentalizing or over-feminizing Christianity drove out the men, and created the current "feminized" church. It might be Bernard of Clairvaux (Podles's bad guy), altar girls (Tony Esolen's focus), or prissy behavior codes (what the iMonk criticizes). One then reasserts the manliness of Christ, of the Old Testament, of God the Father, of the apostles and martyrs, and voila! a complete narrative of declension.

Historically I just don't think this works. Here's a few counter-examples:

1) Ever notice how many unattached women believers are specifically mentioned as being church pillars in the New Testament? Like Lydia in Philippi (Acts 16), the prominent Greek women in Berea (Acts 17:12), and Damaris in Athens (Acts 17:34), not to mention the women in Christ's band of followers. Now given the general tendency of Greco-Roman writings to subsume women under men, I think that if women and men are roughly equally represented in the sources, then women are likely rather over-represented in real life. Rodney Stark's fascinating study of the sociology of early Christianity concludes the same: the legendary New Testament church that conquered the Roman Empire was numerically a woman-dominated one.

2) William of Rubruck was a famous (well, at least famous in the circles I move in) missionary to the Mongol empire (expensive annotated version here; accessible paperback here) in the thirteenth century. Several of Genghis Khan's sons had married women from Christian peoples on the Mongol steppe (Kereyids especially) and several of his grandchildren had been raised by such Christian mothers. But what he found was that few if any of the Mongol men would identify with Christianity or be baptized, but that many of the empresses and princesses did.

3) And outside of Christianity altogether, the Greco-Roman geographer Strabo notices the same thing. He's discussing various opinions on certain verses of Homer's Iliad, book xii:1-6, in which Zeus turns away from the battles before Troy to Thrace (modern Bulgaria) and the nomads beyond:

When Zeus had driven against the [Achaian or Greek] ships the Trojans and Hector,

He left them besides these to endure the hard work and sorrow

Of fighting without respite, and himself turned his eyes shining

Far away, looking over the land of the Thracian riders

And the Mysians who fight at close quarters, and the proud Hippomolgoi ["mare-milkers"],

Eaters of curds [Galactophagoi], and the Abii ["resourceless ones"], most righteous of all men.

Strabo approves of those who say the Abii as "bereft" or "resourceless ones" were naturally most righteous, since it is only money, and economic development generally, that causes injustice. Central Eurasian nomads who live on mares and curds far from the ocean and the commerce that comes with it are thus naturally primitive and just. (It's a bit of a digression, but I can't help but cite him at some length, since it points up the oft-ignored anti-civilization strain in Greek thought, that is remarkably similar to much modern radical thought)

As for the term "Abii," one might interpret it as meaning those who are "without hearths" and "live on wagons" quite as well as those who are "bereft"; for since, in general, injustices arise only in connection with contracts and a two high regard for property, so it is reasonable that those who, like the Abii, live cheaply, on slight resources, should have been called "most just." In fact, the philosophers who put justice next to self-restraint strive above all things for frugality and personal independence; and consequently extreme self-restraint diverts some of them to the Cynical mode of life. . . .

Now wherein is it to be wondered at that, because of the widespread injustice connected with contracts in our country, Homer called "most just" and "proud" those who by no means spend their lives on contracts and money-getting but actually possess all things in common except sword and drinking-cup, and above all things have their wives and children in common, in the Platonic way? [The tragedian] Aeschylus, too, is clearly pleading the cause of the poet when he says about the Scythians: "But the Scythians, law-abiding, eaters of cheese made of mare’s milk." And this assumption even now still persists among the Greeks: for we regard the Scythians as the most straightforward of men and the least prone to mischief, as also far more frugal and independent of others than we are. And yet our mode of life has spread its change for the worse to almost all peoples, introducing among them luxury and sensual pleasures, and to satisfy these vices, base artifices that lead to innumerable acts of greed. So then, much wickedness of this sort has fallen on the barbarian peoples also, on the nomads as well as the rest; for as the result of taking up a seafaring way of life they not only have become morally worse, indulging in the practice of piracy and of slaying strangers, but also, because of their intercourse with many peoples, have partaken of the luxury and the peddling habits of those peoples. But though these things seem to conduce strongly to gentleness of manner, they corrupt morals and introduce cunning instead of the straightforwardness which I just now mentioned.

Far from being some new innovation of the left, the feeling that commerce and development is basically a bad thing, and that "we" (developed and civilized people) are the primary spreaders of this bad thing around the world, is deeply rooted in the classical tradition.

Anyway, back to our topic . . .

Strabo also mentions the view of Posidonius who says that Homer's Abioi ("bereft" or "resourceless folk") means specifically bereft of women. He also says these people in Homer were particularly religious, which draws Strabo's indignant reply:

. . . To regard as "both god-fearing and smoke-treaders [from the smoke of their many sacrifices]" those who are without women is very much opposed to the common notions on that subject; for all agree regarding the women as the chief founders of religion, and it is the women who provoke the men to the more attentive worship of the gods, to festivals, and to supplications, and it is a rare thing for a man who lives by himself to be found addicted to these things. See again what the same poet [Menander, the third century BC comic playwright] says when he introduces as speaker the man who is vexed by the money spent by the women in connection with the sacrifices: "The gods are the undoing of us, especially us married men, for we must always be celebrating some festival"; and again when he introduces the Woman-hater, who complains about these very things: "we used to sacrifice five times a day, and seven female attendants would beat the cymbals all round us, while others would cry out to the gods."

Based on a broad range of historical data and contemporary survey research, Rodney Stark and other researchers have concluded (summary here) that women are generally more religious than straight men. More controversially they also suggest that homosexual men act like women in this respect and homosexual women like men. In other words, any religious body has a natural tendency, if not checked by some other force, to be dominated by women and gay men.

What's the conclusion? Certainly those of us who believe that the Christian religion is about salvation, and that everyone, including high-testosterone jocks, need it, should be more inspired than ever to prevent the Gospel from being captured by the natural inclinations of the fallen heart, to make of it something that simply appeals to the feminine side of our sin-distorted natures. But on the other hand, where church attendance is voluntary, and not enforced by social custom or law, a certain predominance of women is not in itself a sign of spiritual ill-health.

Historically, what has often prevented religion from becoming a pink-color ghetto is the link of religion to the state and ethnicity. To the degree that a given church dominates a state or ethnic group, it then becomes compulsory (by law or social custom) for all, thus masking the tendency for greater feminine interest and participation. It is interesting that Eastern Orthodoxy and Judaism are more masculine in support than western Christianity, at least in the United States. He explained that by saying that they were uninfluenced by Bernard of Clairvaux's feminine spirituality. I wonder rather if the reason that in the United States, these two religious bodies are basically ethnic. If natural religion is strongly linked to the feminine, ethnic and national pride seem to be more masculine traits.

In William of Rubruck's report, he noted that the Mongol men did not wish to be called Christian precisely because they saw "Christian" as the name of an ethnic group:

Before we took our leave of Sartach [Sartaq, a great grandson of Genghis Khan, ruling in the Crimea], the aforesaid Coiac [a Syriac or "Nestorian" priest serving at Sartaq's court] together with many other scribes of the court said to us, "Do not say that our master [Sartaq] is a Christian [although rumor said he had been baptized], for he is not a Christian, but a Mongol." This is because the word Christianity appears to be the name of a race, and they are proud to such a degree that although perhaps they believe something of Christ, nevertheless they are unwilling to be called Christians, wanting their own name, that is, Mongol, to be exalted above every other name [chapter xvi].

If we are going to make religion purely voluntary and divorced from ethnicity or the state, then I think we are going to have to accept that masculine interest is going to be somewhat harder to sustain.

Liberals Really Aren't Nicer or More Altruistic Than Conservatives

As a Harvard alum, I get the Harvard Magazine, which always has something unintentionally amusing, and sometimes has something intentionally instructive.

The following little snippet, in an article on political preferences, is in the latter category. Believe it or not, people still need to point out that being a conservative or Republican is not a form of personality disorder. A new longitudinal studies surprised the study's author with the fact that Republicans aren't disfunctional:

In addition to the influences of family, religion, and demographics, the mysterious chemistry partakes of the force of personality. The Harvard Study of Adult Development (originally known as the Grant Study) is a continuing project that began with 268 men who were Harvard sophomores between 1940 and 1942. The study was conceived in 1937 to identify factors leading to mental and physical health. It has also yielded interesting information about political preferences.

Few of the study subjects, for instance, were moderates; most were either solidly liberal (34 percent) or solidly conservative (37 percent). And their political ideologies were remarkably durable. “The interesting thing about these men is that over time, their politics didn’t change,” says professor of psychiatry George Vaillant, lead researcher of the study. “The Republicans at 25 were still Republicans at 85, and the same was true for the Democrats.”

In 1944, a psychiatrist evaluated the men and assigned them characteristics from a group of more than 25 possible traits. Those who identified themselves as Republicans “are more likely to be practical-organizing and pragmatic. They are ‘Show me, don’t tell me,’” Vaillant explains. “The Democrats are more likely to be cultural, verbalistic, shy, and to have a sensitive affect, or to be ‘thin-skinned.’” Aside from these traits, there’s little to distinguish the two groups. They were equally likely to have happy childhoods and to experience alcoholism, mental illness, and divorce. They were also equally likely to exhibit altruism, which the researchers defined as the ability to use personal difficulties to benefit others, as in the case of a childhood polio sufferer who went on to become a pediatrician to help disabled children.

They did differ in certain ways. The Democrats were more likely to have highly educated mothers. Republicans tended to make more money, and to be less open to new ideas. It’s also worth noting that the Republicans were more likely to be athletes, Vaillant says. He theorizes that the propensity for sports arose because the Republicans “were men of action, not reflection.” But in the end, these differences didn’t matter much; the conservatives and liberals aged equally well. These similarities surprised Vaillant, a lifelong Democrat who says he has never voted for a Republican presidential candidate. “I certainly had all kinds of prejudices, and doing the study got me to change them,” he says. “I thought that the Democrats would be a whole lot nicer and more altruistic, and that wasn’t the case at all.”

The actual distinctions they found are also quite interesting, too, even if neither can be classified as a form of pathology.

The following little snippet, in an article on political preferences, is in the latter category. Believe it or not, people still need to point out that being a conservative or Republican is not a form of personality disorder. A new longitudinal studies surprised the study's author with the fact that Republicans aren't disfunctional:

In addition to the influences of family, religion, and demographics, the mysterious chemistry partakes of the force of personality. The Harvard Study of Adult Development (originally known as the Grant Study) is a continuing project that began with 268 men who were Harvard sophomores between 1940 and 1942. The study was conceived in 1937 to identify factors leading to mental and physical health. It has also yielded interesting information about political preferences.

Few of the study subjects, for instance, were moderates; most were either solidly liberal (34 percent) or solidly conservative (37 percent). And their political ideologies were remarkably durable. “The interesting thing about these men is that over time, their politics didn’t change,” says professor of psychiatry George Vaillant, lead researcher of the study. “The Republicans at 25 were still Republicans at 85, and the same was true for the Democrats.”

In 1944, a psychiatrist evaluated the men and assigned them characteristics from a group of more than 25 possible traits. Those who identified themselves as Republicans “are more likely to be practical-organizing and pragmatic. They are ‘Show me, don’t tell me,’” Vaillant explains. “The Democrats are more likely to be cultural, verbalistic, shy, and to have a sensitive affect, or to be ‘thin-skinned.’” Aside from these traits, there’s little to distinguish the two groups. They were equally likely to have happy childhoods and to experience alcoholism, mental illness, and divorce. They were also equally likely to exhibit altruism, which the researchers defined as the ability to use personal difficulties to benefit others, as in the case of a childhood polio sufferer who went on to become a pediatrician to help disabled children.